“Jezt aber, drinn im Gebirg,

Tief unter den silbernen Gipeln,

Und unter fröhlichem Grün,

Wo die Wälder schauernd zu ihm,

Und der Felsen Häupter übereinander

Hinabschaun, taglang, dort

Im kältesten Abgrund hört’

Ich um Erlösung jammern

Den Jüngling, es hörten ihn, wie er tobt’,

Und die Mutter Erd’ anklagt’,

Und den Donnerer, der ihn gezeuget,

Erbarmend die Eltern, doch

Die Sterblichen flohn von dem Ort,

Denn furchtbar war, da lichtlos er

In den Fesseln sich wälzte,

Das Rasen des Halbgotts.”

“Yet now, in the mountains,

Deep beneath the silvery summits,

And beneath the merry Greenness,

Where the woods shudder to him,

And the rock heads gaze down over one another

Upon him, the whole day long, there

In the coldest Abyss heard I

The youth groaning for salvation;

They heard him, how he blustered,

And railed at Mother Earth,

And the Thunderer, who begat him,

The parents pitying; yet

Mortals fled the place,

For it was dreadful, since he, lightless,

Tossed about in his chains:

the rage of the Demigod.” (Friedrich Hölderlin, “Der Rhein,” p.t.)

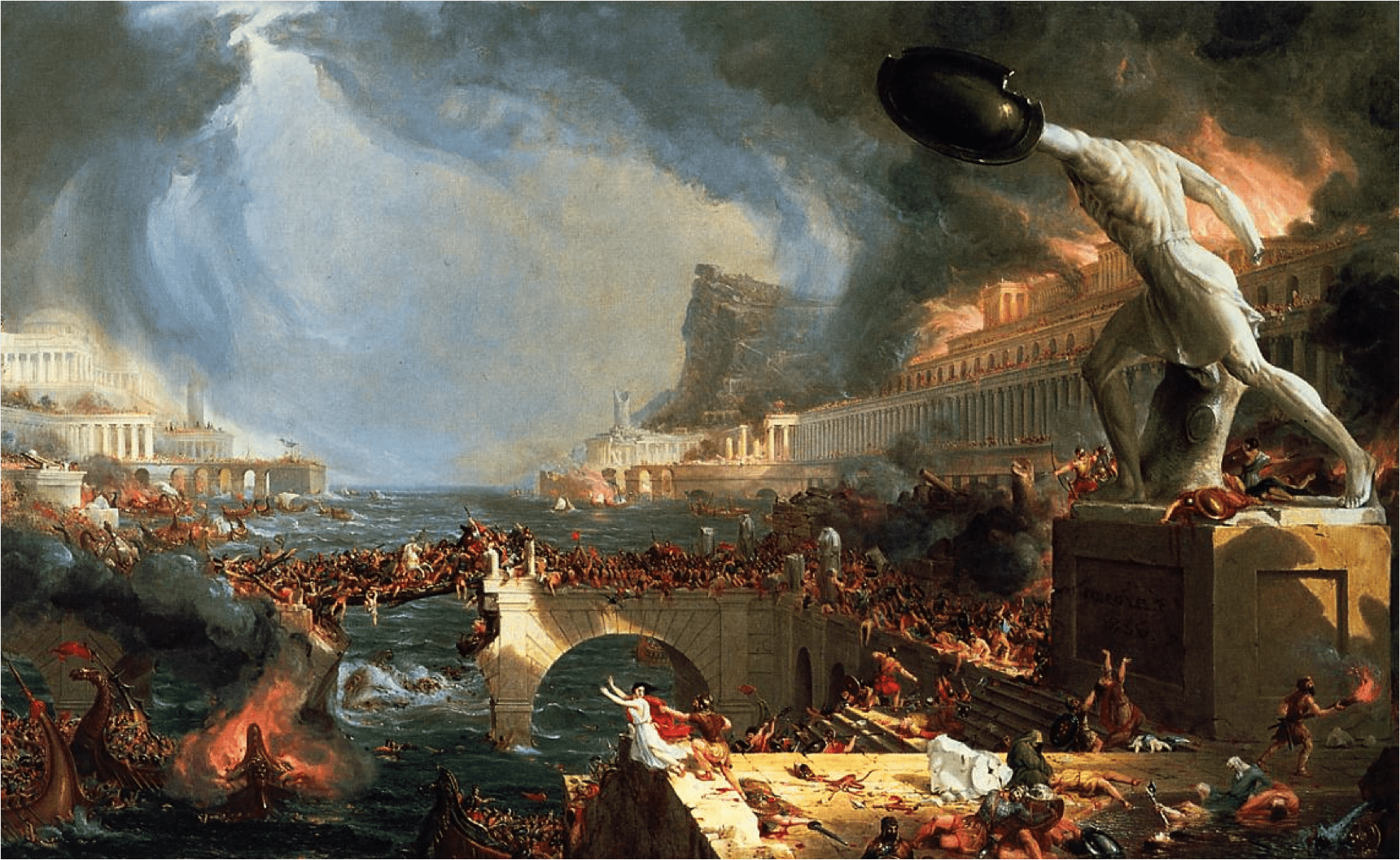

Youth’s high-esteemed vitality, grace in form, and strong, prattling innocence have as their all-too-easy obverses its seething rage, misdirection, and choking, desperate thirst for the authority. The last failing, the outcome is violence. The stuffy back-closet of psychoanalysis has already vomited forth a whole host of “complexes” in the past century to attempt to explain the nebulous workings of the psyche. Jung may find his panacea in dream-analysis, in analyzing anecdotes of young men having their genitals bitten by snakes, and Freud may trawl the muck of the Archaic Greek mythos in search of a new name for the desire to bed one’s twice-removed cousin on the full moon in October. It is all, in truth, quite simpler than that.